Mental Health As A Minorital Gay Man: Walking The Intersectional Tightrope

How do you maintain mental health when it feels like you have to choose between two clashing, intersectional identities?

What is intersectionality?

First, let’s talk about intersectionality, which is a theory that people who are a part of multiple groups or backgrounds face not only the challenges specific to each identity, but also additional challenges from how these identities mix with one another. Intersectional identities, like being gay and of a minority group, expose us to a wider range of perspectives. Unfortunately, the intersection of our identities also can present multiple sources of oppression.

It’s bad enough that some identity traits such as race, religion, sexuality, and gender can set us up for fewer opportunities and more disadvantages in life. But if a person identifies with multiple such traits, they will be more likely to meet disapproval or exclusion at the hands of a group they’re actually part of. An example of this is when people who are cis attack those who are trans of the same ethnic or racial background.

Mental health as a minorital gay man

Why does my being gay equate with shame in the Black community? Why can’t I represent pride for both the LGBT and Black community? And how can people like me, stuck between opposing intersectional identities, mentally and emotionally survive?

I am a black man born into a neighborhood and family filled with “old school” values. But I’m also a part of the LGBTQ+ community, and it hasn’t been easy to try to be myself.

Most of my family thinks of being gay as equivalent to being black in the early 1900s. Not an easy nor desirable way to live. I grew up understanding homosexuality as an invitation for being called terrible names and being bullied, and as something that would keep people from understanding what it truely means to be gay.

In response, as I got older, I eagerly turned to the LGBT community, where I expected to be welcomed with open arms. This hope quickly turned, as I began to see the subtle but noticeable amounts of racism from the community, as well as the lack of diversity. I’d counted on this being “my community,” but I honestly didn’t feel accepted here, either.

Being a minority in the LGBTQ+ community is very difficult because you’re expected to cater to each community’s preferences, and never fully your own. To fit in with the LGBTQ+ community, I felt like I had to tone down expressions of my black identity in order to fit in.

A double life

You live a double life, embracing only your culture around family, and only your sexuality around friends. But you don’t feel embraced by either, if you’re proudly representing both parties. It feels like you have to be someone you’re not to be accepted; and even if you do, you’re still not counted as a full member of either group. Intersectional identities not shared among group members can lead to a divide in their members.

You really want to be a part of both your racial and sexual identities, but because of the common lack of sexual acceptance in traditionally-minded minorital communities, and the racism and prejudice infiltrating the LGBTQ+ community, you can’t. Why not? And how can we change this?

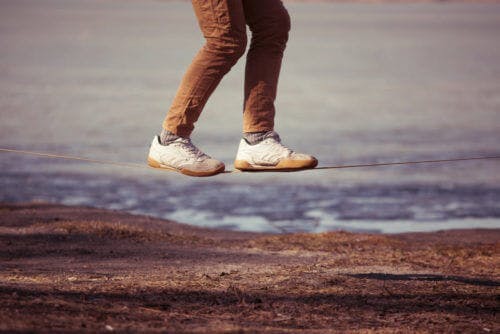

The intersectional tightrope

Through society’s existence, social categories have developed such as race, gender, class, and sexuality. These labels, to some extent, determine how we hang out and socialize with others. They also influence who we consider natural allies and enemies in society.

But how does society interpret people who fit in multiple groupings? And what if you belong to groups that fundamentally threaten one another? How do you live well with two identities that reflect different, clashing values? This is an issue that non-straight minorities have to face, and it’s a major balancing act.

Intersectional hate

Living openly as a gay minority can cause you to be subjected to hate in both communities you belong to; I’ve experienced this myself, and have seen how this lack of acceptance impacts mental health. Minorital gay people, such as myself, can experience long-lasting mental health effects from being unable to live authentically.

And it’s stressful to live within two intersectional identities. For most of my life, being a gay black man meant that I had to be closeted and have a more masculine personality when around family; at the same time, I had to hide that persona away and try to build another, in order to receive acceptance from LGBTQ+ friends.

Homophobia in black and other minority communities

Being a black, gay man has given me clear perspective on the incredible amount of homophobia in black families, neighborhoods, and communities. Growing up in a mostly black neighborhood, I internalized the multiple hurtful homophobic phrases thrown around as a way of casual speech. For example, older family members would use the term gay as another way of calling someone a “coward” or a “punk”.

These people didn’t even need to be referring to me, for it to hurt.

My parents sent messages about the worth of gay people, by how they behaved around the topic. Being gay was so heavily looked down on, it wasn’t even seriously addressed. Just punished, through heavy criticism and turning it into a thing to laugh at and make fun of.

Motivation to deny your intersectional identity

When beginning to come into my sexuality, I denied the possibility of being gay, out of fear of being outcasted. I dreaded rejection from my community and most importantly, my family. This dread arose from ideas instilled in me growing up, in my family and at church.

And while society today has come a long way in accepting other sexualities, there are still communities everywhere–including many minorital communities– where homophobia is a surefire cornerstone of casual conversation.

Conditional love and belonging

Some of these more traditional communities have responded staunchly to changing norms. They’ve doubled down on an “us vs. them” mindset, solidifying outdated beliefs, or even adopting more aggressive ones. Within these communities, children awakened to their own unique identities will want to live out their truth. But they grow up feeling scared and anxious that their peers and loved ones will reject them as a result.

For instance, if a family considers being gay or lesbian a “sin,” it sends kids a message about family expectations. Strict beliefs like this tell children (whether they are gay or not) that they’re only worthy of love, if they are what their parents want them to be.

This kind of conditional love appears in families who choose to enforce years of hurtful traditions, instead of teaching their children to love others regardless of their differences. As a result of this type of early environment, we learn to hide our truth. We learn to put on hyper-masculine personalities, trying to fit the identity our families expect of us.

Believing that you are the problem

Many of our families teach us not to feel shame about the colors of our skin, but make clear they wouldn’t accept a gay child. That leaves you pretending to be someone you’re not, feeling like an imposter within your own home.

Growing up in an unaccepting community, you may come to believe that you are somehow the problem. So you change who you are, in order to secure your family’s acceptance. Their rejection leads you to reject yourself, and to police your own behavior in the hopes of fitting in with others.

My little sister, who is also gay, sums up the pattern of homophobia in Black communities: “I feel that a lot of the Black community are so tied to their Christian values, that they reject us regardless of who we are.” No matter how strong your character is, or how good of a Christian you are, you’re bound to feel rejected due to your sexuality.

I should also mention, that this isn’t just in Black Communities. Religious or tradition-based homophobia exists in many racial, ethnic, and religious communities around the world. Intersectional identity isn’t a hurdle just for Black gay men and women.

Racism in gay communities

When I began to embrace my sexuality, I was excited to finally have the courage to be a part of a community of people who understood me, and who held large community events. This included going to my first pride parade, in hopes of meeting a group of friends who were similar to me. However, there was a familiar obstacle in my way, which has been and likely always will be an issue in my life: race.

The truth of the matter is that in the LGBTQ+ community, white men and women outnumber other races as they do in America. And since racism saturates modern society, minorital gays can expect to experience racism in the LGBTQ+ community as they would anywhere else.

“I believe a big issue is colorism; people of darker complections (especially women) get treated worse overall, so it’s harder to find others who respect us. And that’s including inside the gay community,” shares my sister.

Intersectional assimilation

For minorital gays, code-switching or masking often feels like the only option to gain acceptance. The impulse to assimilate may lead us to do things that don’t feel right for us. We may feel persuaded into living certain lifestyles or expressing an altered identity. “I did find a group to accept me very early on, but then they started pressuring me to do things and go places I didn’t feel comfortable with,” shares my sister.

Lack of representation leads to feeling unwanted

In addition, while the media today pays enough attention to the LGBT+ community, intersectional ethnic and racial representation in LGBT+ coverage is lacking.

“In the LGBTQ+ we don’t have a lot of colored representation,” my sister would go on to say. “So in a way, it gives off the vibe that we are not as wanted within the community.” It gives the impression that only few people can live their truths and have the right to be happy without restrictions; that those who are white can feel comfortable with who they are, but not those of other racial backgrounds.

In a study on gay Black men’s perspectives on the LGBT community, public health researcher Lisa Bowleg conveys that 5/12 gay Black men felt White LGBT communities were uncomfortable with Black gays and expected them to, “assimilate or otherwise accommodate in order to be accepted.”

So, how should we respond? What can we do?

Being a minority in the gay community can be difficult. We try to appeal to those in the communities we were born and raised in, as well as to the LGBTQ+ community that advertises a safe haven for us. But no matter how hard we try, we struggle trying to live intersectional double lives.

Minorital gays face so much on the road to recognition and acceptance as being both an LGBTQ+ member and a proud representative of their racial heritage. As a result, we face isolation from the culture we were born into, as well as from a community that doesn’t usually understand our culture.

Ways to take care of yourself and walk the intersectional tightrope

Dealing with all this, wherever you go, every day of your life, can cause high levels of anxiety, as well as depression or complex trauma. However, there are methods to lessen the impulse to earn approval, and to just take care of your emotional self. Peace in some regard is possible even for those with clashing intersectional identities.

Here are some recommendations of ways to lighten the load. It’s important to try to practice a few of, if not all of these steps for the betterment of your mental health. These methods can not only help you balance your intersectional position, but also help you realize that others walk this path, too.

1. Make a reality-check friend.

Befriend someone who shares the identities you claim. In my case, that was someone from both the LGBTQ+ community and my own race.

One of the biggest impacts on my mental wellness was finding a friend in the LGBTQ+ community who was of my racial background. This gave me an opportunity to talk with someone who perfectly understood my feelings, which helped me see that my issues within the communities were not just mine. Someone who’s been there can immediately relate to how you feel, and can give tips from lived experiences.

Even if you can’t find someone who shares your exact community memberships, folks with different intersectional identities to yours can still provide similar support. They’ll still know the feeling of being torn and misplaced.

2. Take a break from adapting.

Don’t be afraid to isolate yourself from both communities if you need to for a short period of time. Taking time away from the world and being alone or with others you don’t have to worry about working to impress or adapt to is stress relieving, and gives you the chance to take a breath and to relax. You’ve been squeezing into all kinds of different molds, so this is a chance to bounce back and spend time with your authentic self.

3. Consider how you can use your position.

Being a part of multiple communities that are looked down upon can damage one’s physical mental health. But those impacted by intersectional discrimination are likely to develop empathy and acceptance towards others who have been outcast or shamed for their identity. Because of our intersectional identities, we’ll be better at relating to people, and as a result will be better at having those people relate to us.

4. Put dating on pause.

When you put yourself out there to receive love and attention from others, you also open yourself up to judgement and stereotypical remarks. If you’re trying to gain confidence in your intersectionality, dating may prove triggering and difficult.

If you’re afraid of becoming more distraught from rude remarks, don’t be afraid to take a dating break. Instead of dating, enjoy spending time relaxing, or nurturing existing positive relationships in your life.

5. Consider coming out if you haven’t.

I struggled with coming out to my family, since I believed they’d place their homophobic values ahead of their love for me. So to begin testing the waters, I told a few of my closest friends at the time. Eventually, I went on to tell more accepting members of my family. And eventually I brought my siblings into the loop. Gradually building a circle of trustworthy loved ones made me feel less alone. It was a step closer to feeling like I fit in.

Coming out, though, is definitely just a suggestion. A very very small suggestion. Not everyone has the opportunity to come out of the closet, straight into the accepting arms of family or friends.

If you don’t feel comfortable coming out just yet, there’s no rush to do it. But while your family may seem stuck in their ideals, you could be surprised. Sometimes, families have trouble carrying on discriminatory traditions, when they know it hurts one of their own. Some families may be able to grow and change their beliefs. And if they don’t know how, then maybe they’re willing to learn, with your help.

6. Decide if trying to fit in is worth it.

Say none of the suggestions I mentioned above work for you. Maybe they’re just not possible, or maybe you just can’t help pleasing others to fit in. At some point, you eventually need to ask yourself….is it really worth all of this effort toward gaining acceptance?

Yes, this may really be a worthwhile question to ask. If you could live your truth, comfortably, without caring what others thought–wouldn’t that be great? It’s easier said than done, but as of writing this article, I’ve been trying to lessen the masking impulse. This has involved resisting the inclination to force myself into either a gay or Black mold. I don’t have to be a model member of either community; I’m just connected to both by my own personal interests.

Your intersectional self is valid, no matter what.

What I’m getting at here, is that you are valid without having to be someone you’re not, especially if the effort drains you or induces stress. Sometimes, instead of worrying about falling off the intersectional tightrope, it makes more sense to voluntarily step off. Remember that you are valid no matter your race, gender, or sexual orientation, and that it’s not always worth catering to the opinions of others.

The tightrope to manage your status in both communities may be a major burden to bear; but one thing you need to remember is that you are not alone. There are plenty of minorities in the LGBT community who understand what you’re going through. People who understand will be there for you if need be, and there is no need to force yourself inside of stereotypical margins.

This article is part of Supportiv’s Amplify article collection.

Contact Us

For anonymous peer-to-peer support, try a chat.

For organizations, use this form or email us at info@supportiv.com. Our team will be happy to assist you!