Nowadays, we see trauma as a potential response to any kind of event that overwhelms our internal and/or external resources to cope–even momentarily.

In an age where stressors are at all-time highs and our coping abilities are at all-time lows, trauma applies to our society on a much broader scale than ever before.

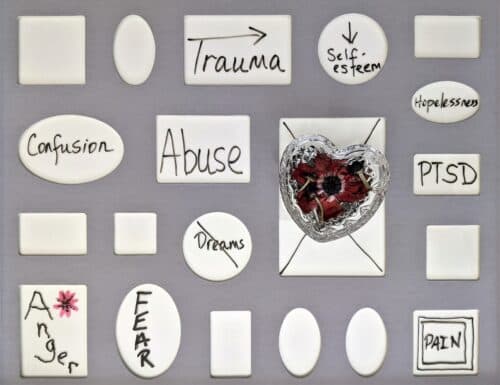

Ranging from mass pandemic trauma to a modern understanding of microtrauma, we’ve all got to adjust our view of what “counts.” What kinds of trauma exist? And what kinds of symptoms can be associated with it?

Types of trauma, as we define it in modern times

Complex Trauma (CPTSD)

Complex trauma, also known as developmental or relational trauma, has been recognized as another form of post-traumatic stress in recent years. Just like the major, single-episode trauma we associate with “shell shock,” repeated non-violent abuse can produce equally disruptive PTSD symptoms. This kind of trauma often arises from dysfunctional family dynamics, emotional abuse, religious abuse, and systemic mistreatment.

Racial Trauma

Fetishization and racial prejudice are traumatizing on their own. But in our current age, we are seeing acts of actual racial violence at a higher rate than ever. Racial trauma causes hypervigilance and exhaustion due to the constant risk of aggression, violence, and unjust treatment.

Pandemic Trauma

During the pandemic, we all faced uncontrollable events that could mortally impact our life and livelihood–if they didn’t actually do so. The pandemic has forced us all to confront loss, uncertainty, and helplessness in ways we never have before. How many of us developed coping mechanisms and behaviors during this time that just don’t work in the “normal” world? This mis-match between coping mechanisms and the environment makes us especially vulnerable to experiencing trauma.

Occupational Trauma

As part of the pandemic, healthcare professionals and other essential workers experienced occupational trauma en masse. Essential workers have been simultaneously underpaid, undervalued, underprotected, and subjected to daily abuses. All without the leverage or financial freedom to demand better conditions. You couldn’t be blamed for internalizing this experience. But outside of pandemic conditions, occupational trauma has always been a real risk for folks in various professions.

Trauma-related symptoms

Fawning

Also known as people-pleasing. Subverting your own needs in order to keep the peace is a common and under-recognized response to trauma. If you learned that expressing your real thoughts and feelings caused an attachment figure (parent or partner) frustration, you might have learned to stop expressing them.

Alternatively, fawning patterns can arise when you internalize that you’re only lovable when happy, smiling, or otherwise people-pleasing.

People with fawning tendencies from trauma can benefit from boundary-setting practice.

Dissociation

Also known in some of its forms as freezing or zoning out. See also depersonalization and derealization. Amnesia, paralysis/loss of sensation, flashbacks, and tics can all arise (at least partially) from dissociative processes.

Controlling behavior

When you have experienced others’ abuse of power, you may feel driven to stay in control. This is an attempt to prevent harm, and it stems from a belief that if someone else is in control, they will inevitably hurt you. Consider the role mental time travel may be playing in your drive to control.

Armoring

Armoring, clenching, or all-over muscle tension is known to correlate with a history of trauma (even relational trauma or microtrauma).

Catastrophizing and rumination

After a traumatic experience, we tend to subconsciously make assumptions about how we could’ve prevented what happened. Trauma can create a belief that if you had just prepared better, you wouldn’t have been traumatized.

This is a form of blaming oneself, and that self-blame places a major responsibility on your shoulders. How can you expect yourself to anticipate and prevent any kind of negative experience? Trying to do so is called catastrophizing, and it’s a natural but unhelpful response to trauma.

Self-isolating

You may avoid events, in-person gatherings, text messages, calls, or visitors due to a fear of what will happen–because in the past, these connections have come with negative emotional consequences. Believing that people are dangerous, you avoid the risk altogether.

Rejection sensitivity

“Rejection sensitivity, also known as rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD), describes intense distress in response to even minor or perceived rejection. We all dislike rejection and can become upset by it, but to those struggling with rejection sensitivity, the emotional response to perceived rejection is extreme and debilitating. Any sort of exclusion, criticism, rejection, or judgment from others can lead people with RSD down a rumination spiral. People with rejection sensitivity also tend to overestimate how much people dislike or judge them…

“Early life experiences that can predispose people to rejection sensitivity range from rejection by peers to neglect and abandonment by parents.”

Inability to apologize

You may fear that if you give an inch, they will take a mile. If you apologize or admit fault, your trauma has taught you that vulnerability will be used against you. However, in healthy relationships, apologies only create mutual validation, trust, and understanding–even if you’re the one giving the apology.

Feeling triggered

Suddenly feel a flood of emotions that don’t fit the current situation? It’s normal to feel triggered or to “flashback” when you’ve experienced trauma. Flashbacks don’t always look like images from a movie interrupting your consciousness. They don’t always involve screaming and confusion.

The most insidious types of flashbacks may be the ones you don’t realize are happening. Emotional flashbacks occur when a situation or interaction triggers your brain’s social and emotional protective mechanisms. They can look like:

- going blank or shutting down in a heated argument,

- believing someone thinks something about you even though their behavior doesn’t indicate it,

- intense fear of abandonment without credible evidence,

- inability to stop eating, watching tv, using substances–a feeling of unquenchable desire,

- impulse to make yourself physically small (hunching over, clenching),

- unexplained feeling of rage,

- intense defensiveness,

- uncontrollable sleepiness without reason

Once you start to notice trauma in your world, what should you do with it?

There is no need to open Pandora’s box without professional guidance. You don’t have to sit down and pore over your life’s story, studying each and every instance of trauma in your past.

Rather than re-traumatizing yourself in the flood of old memories, shoot for post-traumatic growth. Focus on what you took away from the trauma–not on the traumatic event(s) itself–and how those takeaways show up in your life now. How can you adjust your assumptions, your patterns, or your life to better address the lasting impacts of your trauma?

Browse resources that address your experience in Supportiv’s Trauma article collection. Or chat with peers who won’t invalidate your story.

Did we miss a category of emotional trauma that you identify with? You can always drop us a note at info@supportiv.com.

Contact Us

For anonymous peer-to-peer support, try a chat.

For organizations, use this form or email us at info@supportiv.com. Our team will be happy to assist you!